A BODY OF RELATIONS

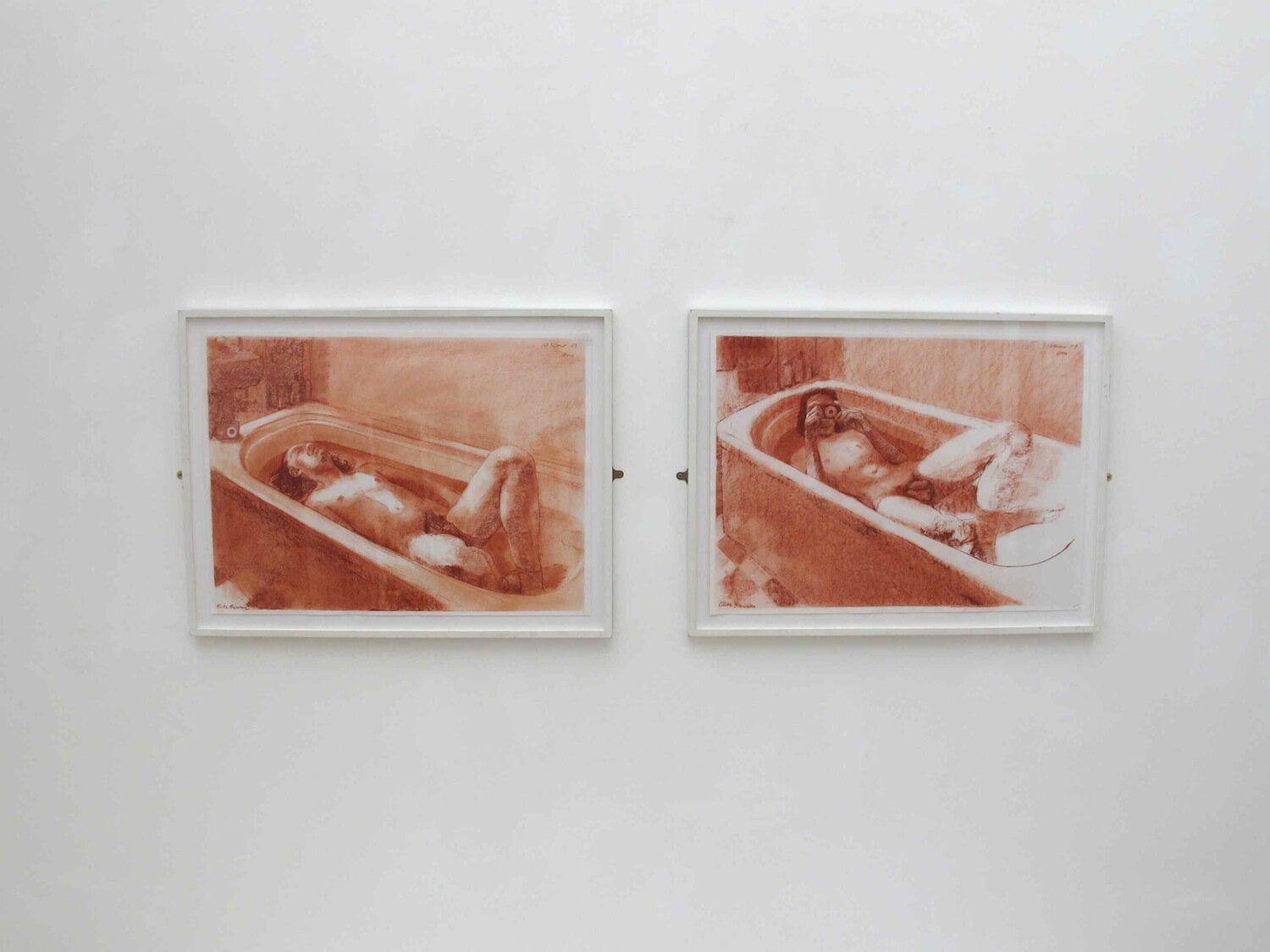

A Body of Relations: Reconfiguring the Life Class, viva exhibition at the University of Lincoln, 2016

About A BODY OF RELATIONS: Reconfiguring the Life Class

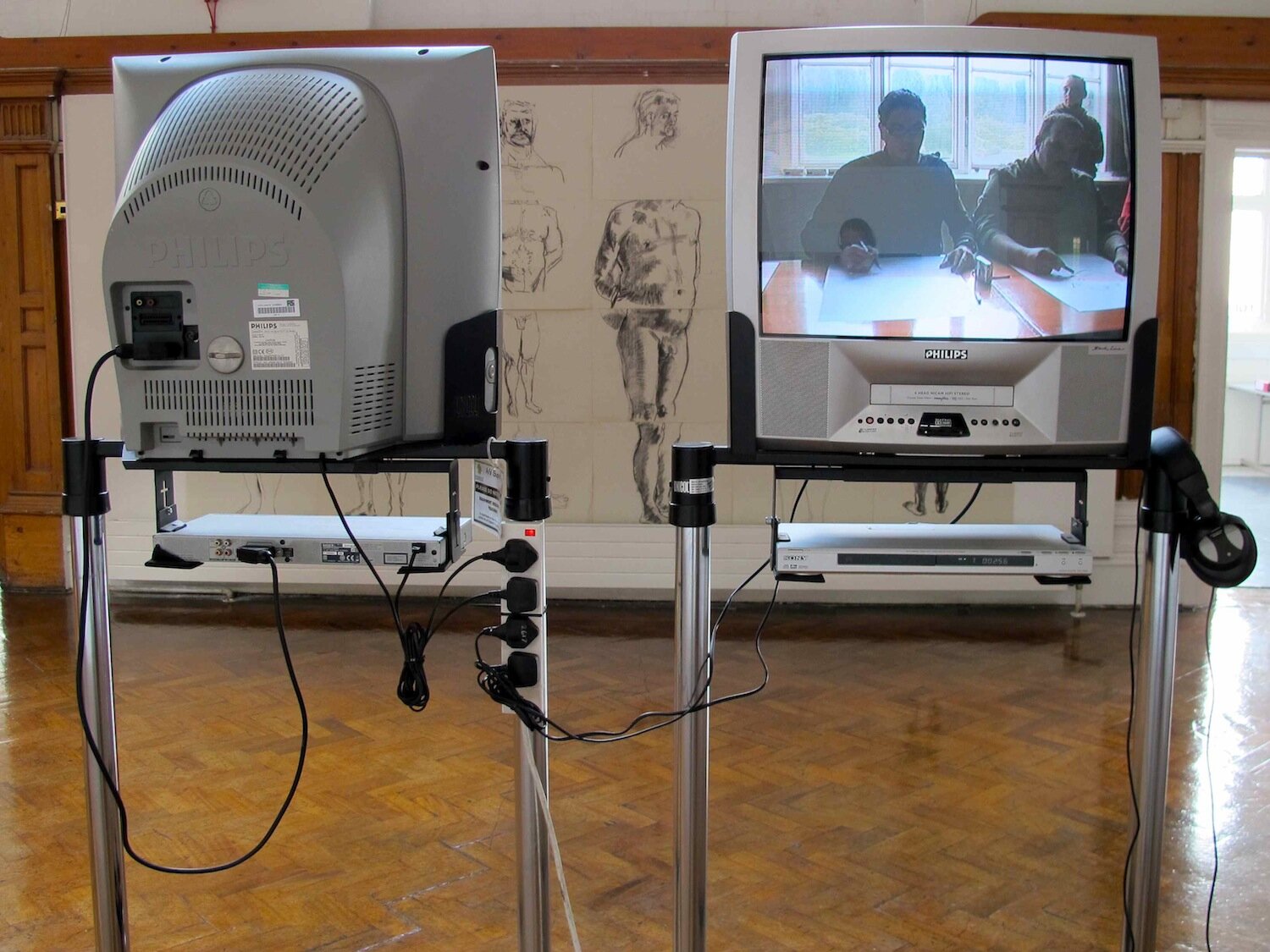

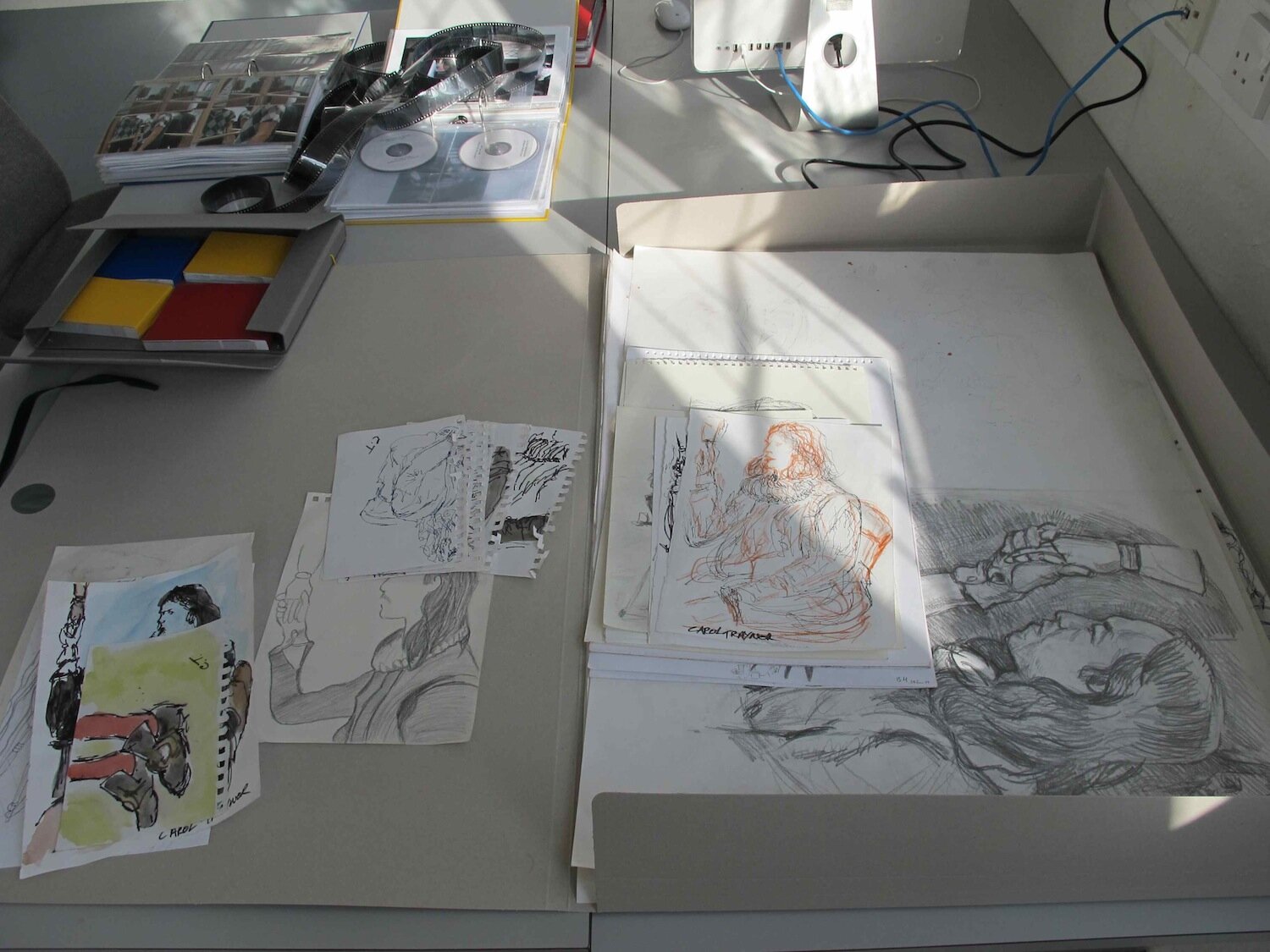

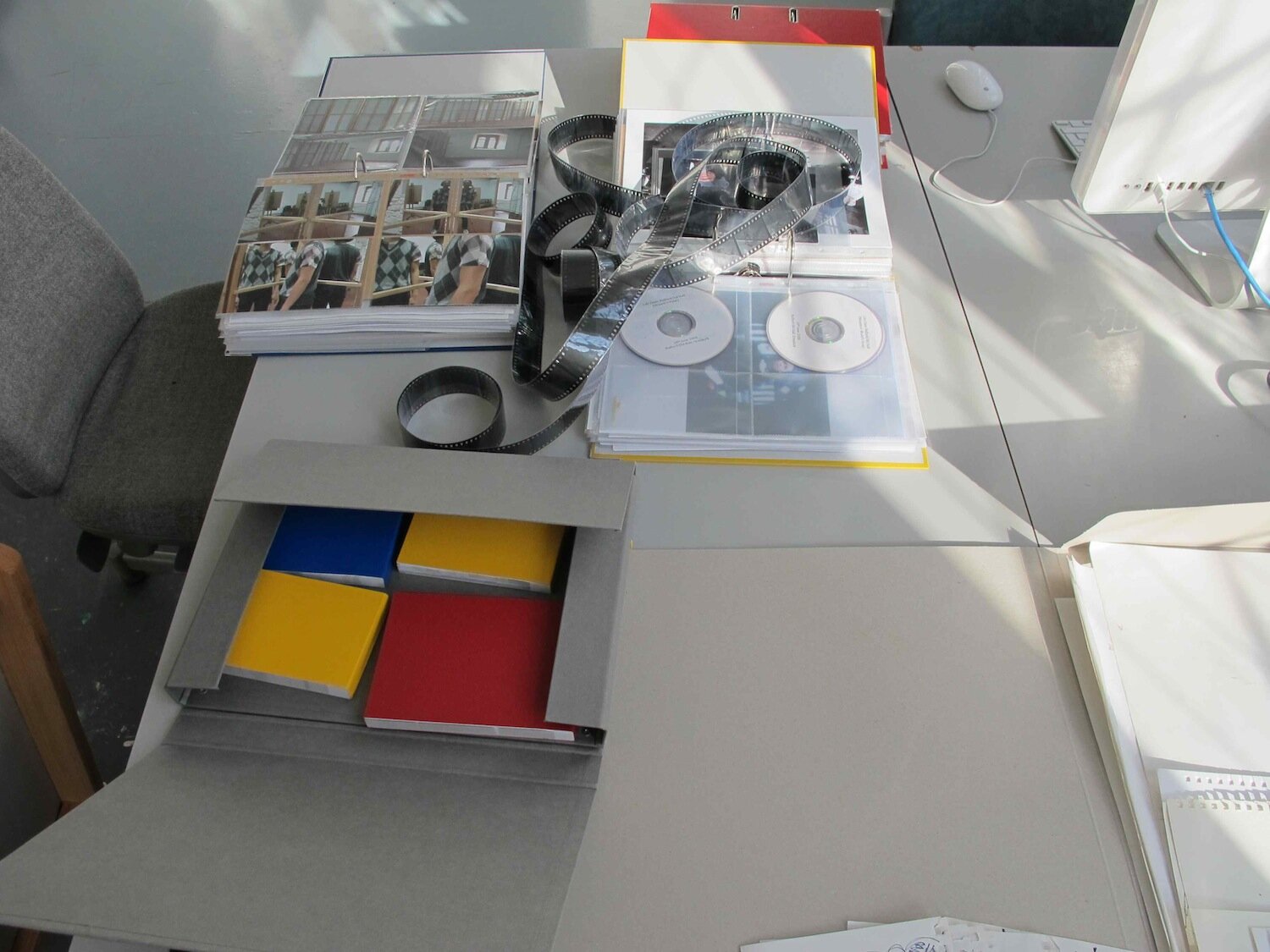

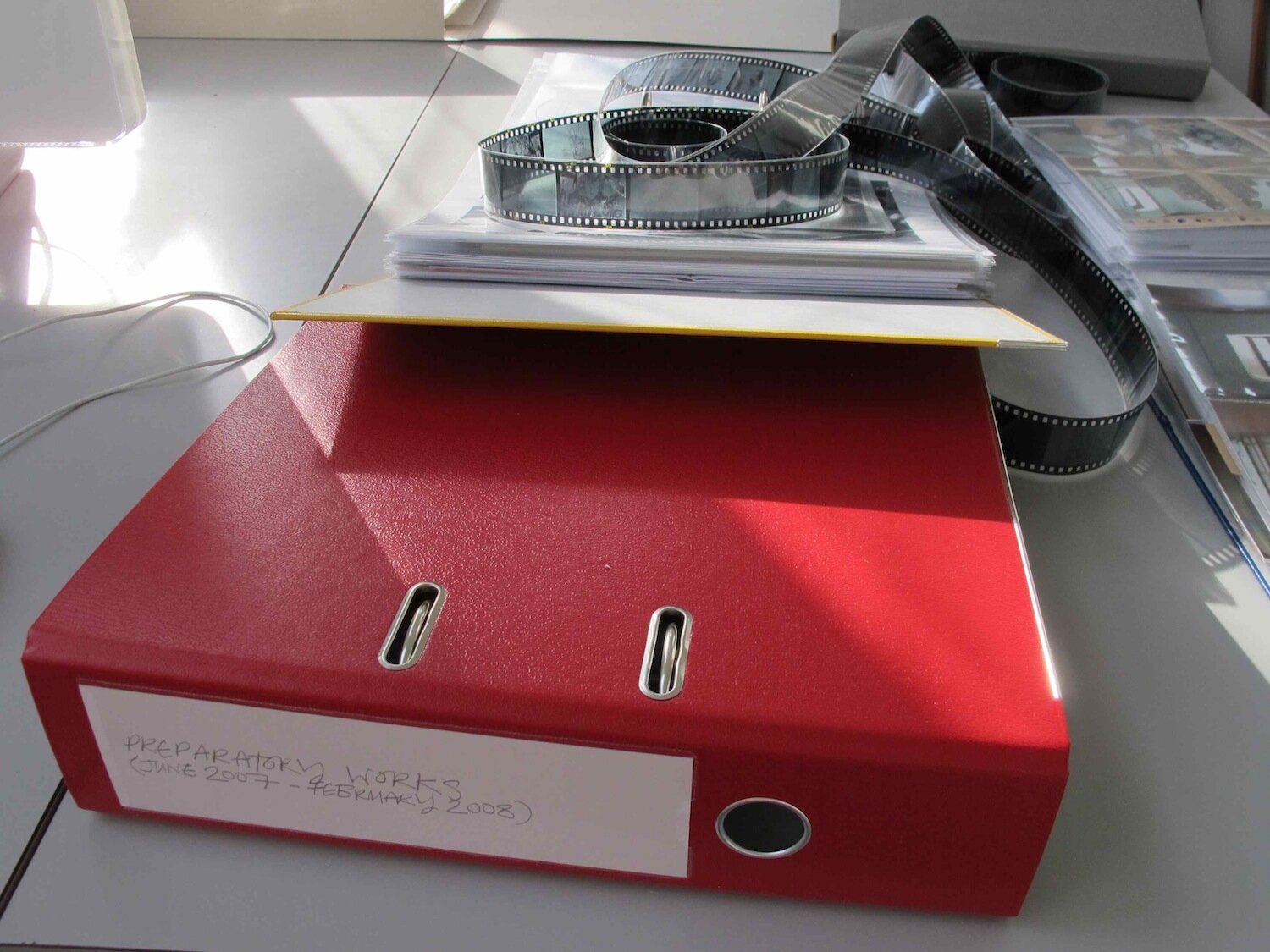

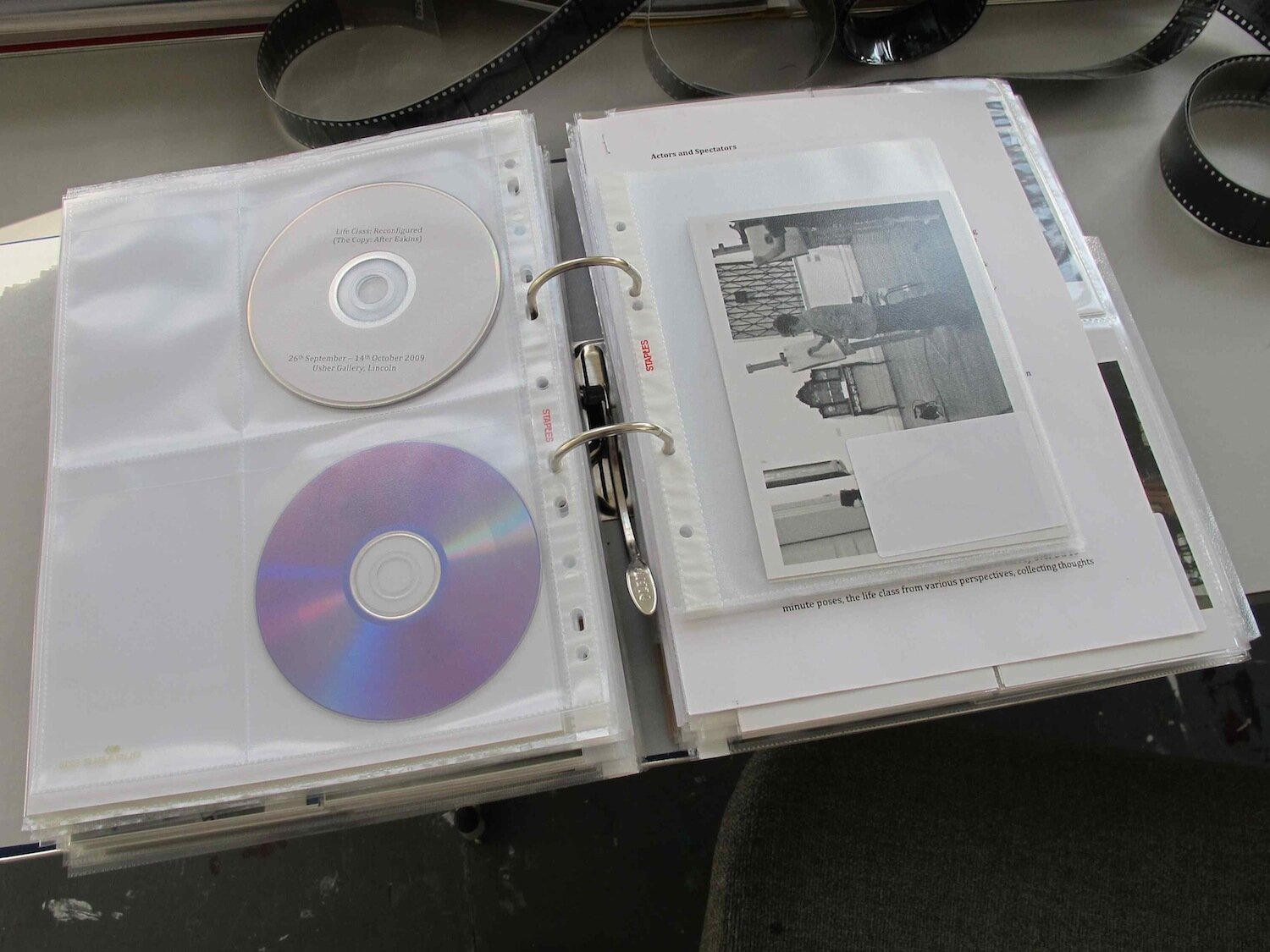

Part of my Fine Art PhD by Practice at the University of Lincoln, this period of work made between 2007-2010, used the foundations of earlier work exploring the conventions and traditions of the academic life drawing class and role of the life model as the basis of the research enquiry e.g. “The Model Curator (Life Class series No.1)” (2004). The research developed three phases of work 1) Preparatory Works, 2) Life Class Series, and 3) The Reconfigured Life Class, each rethinking the conventional roles and relationships of the artist, model and tutor in the life drawing class, and the subsequent status of drawing, photography and video as forms of documentation.

-

Abstract

The established practice of drawing from the life model elides the complexity of the life model in relation to gender, race, social status, sexuality, and identity. As a pedagogical methodology, the assumptions and protocols of the life class enforce separation and silence between the life model, participant-artist and tutor, and uphold a framework of oppression[1]. Further, this form of education is widely viewed as outmoded, neglected and of little relevance to contemporary art practice.

As a practicing artist, I want to re-examine the relationship between life class practice and the theoretical positions of contemporary art practice. Theoretically, the challenge of this research, to the established practice of the life class is premised upon several concepts. Firstly, the “dematerializing of the art object”[2] the process rather than art object as the primary site of the artist’s creative output. Secondly, the concept of ‘performance’ art where the artist’s body becomes the potential primary site of the artwork. Thirdly, Bourriaud’s ‘relational aesthetic’, which posits other people’s participation and engagement with the artwork’s “inter-human relations”[3] as the principle by which an artwork is mediated.

In this practice-led research, I examine the notion of the artwork as ‘event’, and the subsequent ‘art object’ as document, artifact, or ‘trace’[4] of the artist’s and other participant’s performativity; whether invited, co-opted or usurped into the artwork. The research is undertaken through the production of a portfolio of original new artworks and their reflection and written analysis. I examine the following lines of inquiry[5]:

1) To understand the implication of a process-orientated ‘performance’ and ‘participatory’ art practice to challenge the conventions of the life class

2) To explore the subsequent effects of this reconfiguration of the life class on our understandings of the role of the life model, and their subjectivity that the conventional life class elides

3) To examine the role and status of performance and participatory art’s documentation process on the life class, and the life drawing

4) To re-consideration the educational possibilities of performance and participatory art practice on the teaching of the life class.

I adopt a recognized multi-mode approach to evidencing this inquiry using videos and photographs, qualitative interview, historical research and strategies of display[6]. My research develops a theoretical trajectory to assert that contemporary art practice enables a return to the life class, but to a reconfigured life class which has learnt from the issues of power, play and subjectivity examined in this practice and commentary.

The reconfigured life class provides a performative, discursive, social space to empower the life model to actively engage in the production of his/her own self-image. In addition the research re-frames the life class as a site in which the discourses of contemporary art as ‘relational’ can reach its apotheosis as a de-materialized performance event, whose trace exists in the dispersed materiality of the participant-artist’s body and whose silenced subject, the life model, becomes a full individual subject.

-

[1] Freire, Paulo, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, translated by Bergman-Ramos, Myra, Penguin Books, edition 1996

[2] Lippard, Lucy. Six Years: The Dematerialization of The Art Object from 1966 to 1972. University of California Press Ltd, London, 1997

[3] Bourriaud, Nicolas, Relational Aesthetics, Translated by Pleasance, Simon & Woods, Fronza, with the participation of Copeland, Mathieu, Les Presses Du Reel, 2002

[4] Benjamin, Walter, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction in Illuminations, Pimlico, London 1999

[5] Nelson, Robin, Practice as Research in the Arts, Principals, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, New York, 2013, p.26

[6] Ibid, p.26

A Body of Relations: Reconfiguring the Life Class, interim exhibition at the University of Lincoln, Greestone Building, 2011

-

Special thanks to the University of Lincoln; my supervisors (past and present) and research environment, Catherine George, Steve Dutton, Alec Shepley, Deanna Petherbridge, John Plowman, AAD PhD Forum, the Graduate School and Kathleen Watt; collaborators, curators and facilitators (in chronological order), Louise Adkins, Peter Bevan, Richard Black, Maurice Carlin, CFCCA (Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art), Emma Chambers, Clare Charnley, Celia Cross, Paul Harfleet, Rachel Jane Holland, Mark Houldershaw, Stephen Iles, Hilary Jack, Alhena Katsof, Sally Lai, Penny McCarthy, Benjamin Merris, Alicia Pattyson, Jonathan Purcell, Hester Reeve, Lesley Sanderson, Transart Institute, Transmission Gallery Committee, Maggie Warren, Jeremy Webster, The Wellcome Collection; interviewees Jeremy Deller, Stephen Farthing, Alan Kane, Emma Osbourn, Donald Smith, Ming Wong; advice and supporters Peter Bevan, John Calcutt, Marko Daniels, Colin Fallows, Jerome Harrington, Anthony Key, Beccy Kennedy, Sharon Kivland, Jasper Joseph-Lester, Jonathan Purcell, Michelle Sissons, Andrew Sneddon, work colleagues at Sheffield Hallam University Fine Art department, dearest and patient friends and family; all participating life drawers and finally many thanks to life models Ashley, Kevin, Liz, and Marissa without whom this research could not have happened.