PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST

After the Birth of Painting

single screen monitor, video loop 2006.

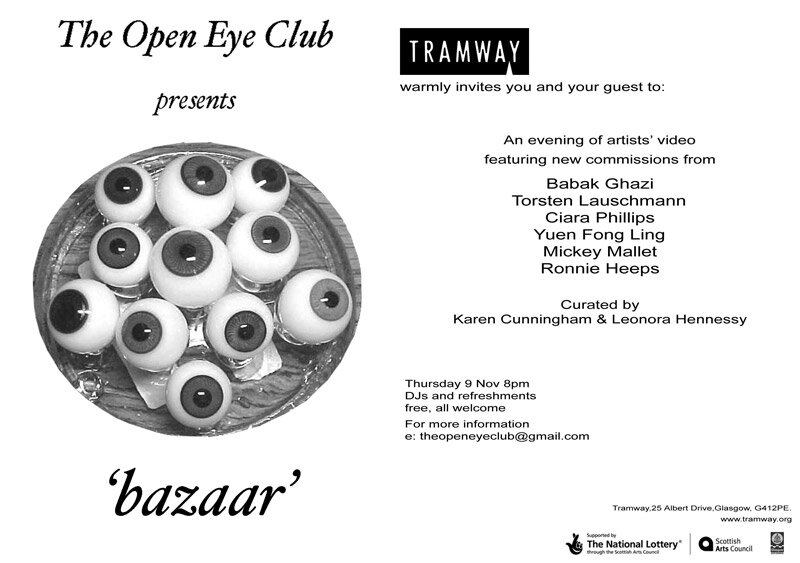

Feature in "Bazaar", Open Eye Club event at Tramway Glasgow on Thursday 9th November 2006.

-

The Open Eye Club presents bazaar at Tramway 9th November 2006 Notes on Context Essay by Sarah Smith

On considering bazaar, the latest offering from The Open Eye Club, a nascent exhibition forum for video art, some familiar art historical predessessors come to mind, both in terms of exhibition context, and the individual works shown. This is not to suggest that the exhibition can be conveniently situated within the postmodern regurgitative frame, but that it reflects a dominant tendency in video art to negotiate a relationship with the pasts that haunt it. From its emergence as a distinct medium in the 1960s (heralded by the work of Nam June Paik) video has challenged the ubiquity and limitations of its moving-image forebears, television and cinema, as well as investigating its place within the broader history of art.

The Open Eye Club exhibitions are more appropriately described as events, and comprise of one-off showings of artists‘ video (in the case of bazaar works were commisioned by the Open Eye Club curators, Leonora Hennessy and Karen Cunningham predominatley from artists for which video is not their main medium). Though not a film or video club in the sense of being an artists‘ alliance, the events borrow features from the prototypical avant-garde film collectives, in particular screening new work, and facilitating discussion. The event, then, becomes the central mechanism of The Open Eye Club‘s curatorial practice. Emphasising experimentation, both in terms of the work made and its exhibition, further relates aspects of these events to the film clubs that were the locus and platform for many of the most innovative film and video works in both the UK and the US in the 1960s and 70s, notably The Filmmakers Cinematheque in New York and the London Filmmakers Co-operative.

While these earlier collectives were generally centered around cohesive avant-garde film movements, there is little to connect video art of recent years. (Perhaps this accounts for the lack of cogent video art equivalents to rival the film co-ops of the 60s and 70s.) Indeed, as noted by film theorist Michael O’Pray amongst others, possibly the only unifying feature of video art today is its irreverent looting of the images of the past.

Each of the six films commissioned for bazaar are markedly different, and it is primarily as a group, in the miscellany of articles displayed, that they relate to the imaginative space of the bazaar, from which the event takes its title. Like the marketplace it evokes, bazaar presents its audience with an assortment of goods, and (most likely inadvertently) borrows another implied meaning of bazaar in that The Open Eye Club’s events, in keeping with their general ethos, is driven by a kind of altruism, with those involved often ‘donating’ time and work to benefit a cause. The ‘cause’ here is not only the obvious one - providing artists with an opportunity to make and exhibit video - but also provoking discussion between the artists and others.

The significance of moving image media to the history of art is indisputable. High profile film and video art exhibitions are commonplace in museums and galleries today, and an increasing emphasis on high production values brings this art closer to its mainstream counterparts (which, at times, is a parodic strategy). Artists such as Pipilotti Rist, Douglas Gordon, and Matthew Barney offer us an expensive spectacle that emulates Hollywood (which is part of its point). Yet video also remains one of the most accessible, cheap, and immediate forms of art there is. The Open Eye Club normally operates on no budget (with bazaar at Tramway and Totally P.C. in Gi as exceptions) and show work for one night only, demonstrating the valuable contribution that a non-precious, low-fi approach can make to experimental video art. Moving image art has cemented its place at the centre of contemporary art practice, making those activities that still navigate the periphery all the more essential.

Notes on the Videos

In one way or another all the works are involved in an investigation of the past while attempting to maintain the possibility of experimentation, and somewhere in the tension between those conflicting pulls is the drama that animates the most compelling contemporary moving image art. It is a testament to the assured place of video in the canons of art history today that we can identify precursors for most of the works in the show, and, like much moving image art since Warhol, many of the videos are engaged in various critical revisions of dominant imagery from both the history of art and pop culture.

Ciara Phillips’ ‘Chick Flicker’ and Babak Ghazi’s ‘Work in Progress’ both use video to present a succession of related pre-existing images, although each work does so very differently. In Phillips’ video the simple act of flicking through the pages of a book, and the attendant sound of the paper scraping against a thumb, denotes the transition from one image to another as snippets of images of seminal feminist art by Valie Export, Hannah Wilke, and Adrian Piper, amongst others, enter the frame momentarily. The brevity of the video and the speed at which pages are flicked suggest a disenchanted gaze, rather than an engaged reader, and reflects a culture of fast visual fixes, paralleling this book and the work it contains with a glossy magazine (Harper’s Bazaar?) that one carelessly browses through. The video thereby obscures distinctions between high culture (and the legacy of these important artists) and pop culture, a levelling out that is further underscored by the postfeminist connotations of the work’s title.

Ghazi’s video ‘Work in Progress,’ seams its images together by the more conventional use of the dissolve and, coupled with slight zooming into and out from certain images, creates a mesmeric visual essay of sorts. Comprised of a series of portraits and performance images culled from both pop culture and art, the film harks back to the decadent New Romantic cinema in the 1980s, which was intensely interested in the theatre and spectacle of sexuality and sexual imagery. Ghazi’s work reflects “an interest in the creative and economic freedom of the individual to construct his or her open idenity“. “The insertion of the well-known photograph of the writer and critic André Malraux surrounded by a selection of images that he used to illustrate his concept of the Imaginary Museum, informs us that we are privy to Ghazi‘s own personal version of the same. His particular museum of the mind is flooded with images that articulate the perfomativity of gendered identity from the vast repertoire available to us. The film’s use of the graphic match (much loved by Hollywood) that searches for formal similarities between two connecting shots softens transitions and adds to the seductive, trance-inducing effect of the video overall.

Hypnotic reverie is also effected by Ronnie Heeps’ sensorially uplifting ‘Whatever Happened To.’ The film quickly completes the question with the introduction of its first image which seems to ask the viewer “Whatever happened to ... kaliedescopes?“ Using a version of Ravel’s Bolero that fuses many musical styles to accompany his explosive imagery, Heeps produces a psychedelic ballet, reminiscent of both the 1930s experimental films of Len Lye and Busby Berkeley’s Hollywood musicals of the same era. Glimpses of flowers and faces move through the colourful wheels of Heeps‘ video revealing the source material of this work which he playfully refashions into a digital kalidescope.

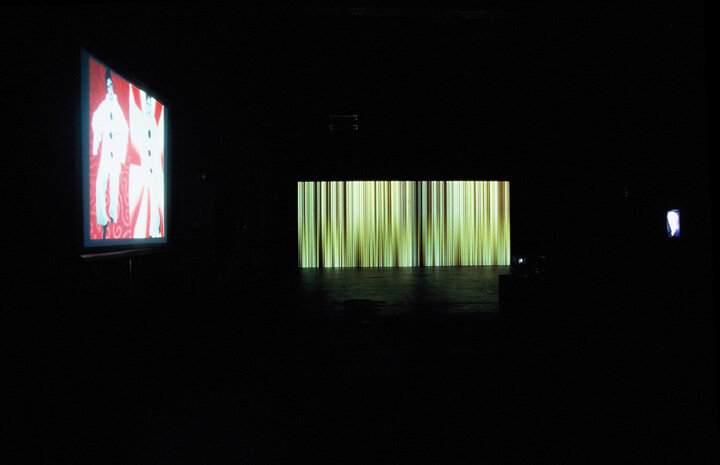

While Heeps‘ video and ‘Curtain’ by Tortsen Lauchmann come closer to abstraction than the other pieces, they resist the pure abstraction of some of the work they recall, such as the short painterly films of Stan Brakhage or Len Lye. As already noted, Heeps recombines found imagery to create abstract patterns, leaving recognisable traces that trail through his video, while Lauchmann’s title announces the real-world object that his abstract projection resembles. Interestingly, however, while it may approximate a curtain it is, in fact, a digital image produced by enlisting the mathematical rules of Cambridge Mathematician John Conway’s ‘Game of Life‘ (1970). Conway’s game comprises an initially selected configuration of cells that then evolves independent of any further human input. Combining the idea of the automaton with the notion of the digital curtain, which is currently used to describe anything from firewalls that prevent computer viruses to the ability of web users to conceal their identity online, Lauchmann’s film foregrounds the more threatening aspects of digital culture. By also referencing abstract painting of the mid-twentieth century ‘Curtain’ freezes the present in a moment of simultaneous looking forward and looking back, stuck between anxiety and nostalgia, sagely pondering the ‘in between‘ place of video art today. The possibilities of experimentation promised by new media are at once embraced and thwarted here by the use of technology to manifest a foregone conclusion. And yet, the resulting large projection, far from foreboding, is intruiging and stunning.

‘After the Birth of Painting‘ marks Yuen Fong Ling’s first exhibition of video work. Although viewed on a monitor turned on its side, the image appears upright, signalling the first stage in a process of defamiliarisation. The front half of a plaster mould is encased by the frame of the monitor, the impression of a face faintly distinguishable inside its thick edges. Projected onto this is a pink-tinted image of a woman who appears to be engrossed in an act of painting or drawing and, as she turns to look at her subject before returning to her drawing, her face maps perfectly onto the outline of the concave plaster face. Looking directly at us, yet mapped onto this other face, we are unsure of who or what she is painting - the mould, herself, or us. The much discussed ‘mastery of the gaze‘ implicit in many images of women, from nude painting to Hollywood cinema, is here hijacked and confused. Contrasts between the two portraits abound. The pallid stillness and opacity of one face contrasts sharply with the warmth, movement, and transparency of the other. Neatly implicating the established media of sculpture, painting and drawing, video coolly observes its ancestors and throws established looking patterns into question.

Micky Mallet’s film, ‘A Friday Night In,’ dramatises the essential challenge that The Open Eye Club sets for many for the artists in bazaar - how to use video as part of a broader practice, or how to make a video when you’ve never made one before. Or, in this case, how to enjoy an evening with friends while mulling over said challenge, and reviewing experimental footage shot earlier, and having a few beers, and trying out partially understood exotic phrases, and resisting the urge to gossip. Mallet collaborates with his two friends Jason Nelson and Derek Lodge while sitting on a couch in his living room, and the resulting work is both hilarious and strangely reminiscent (strange that it is reminiscent) of some examples of modernist cinema that foreground the mechanics and process of making a film in order to demystify cinema and break its illusionistic spell. From Dziga Vertov to Jean-Luc Godard modernist filmmakers have used various strategies to reveal the illusionism and artifice of cinema. In Mallet’s video this is achieved by filmming what should be ‘behind the scenes’ discussions that centre on how to make a video, and also by showing and referring to the video equipment in the room. This film kick starts bazaar’s evening‘s screenings with suitable noblesse oblige by inviting the audience to sit with its protagonists and share in their meandering discussions over a drink.

Sarah Smith is a lecturer in Historical and Critical studies at Glasgow School of Art.